One of the war artists who produced some of the most iconic paintings of the First and Second World War was the renowned Paul Nash and now the Tate Britain gallery have staged an exhibition of his work, including many of his world-famous war paintings reports Sarah Warren-MacMillan.

PAUL NASH (1889 - 1946) is one of Britain’s best-known war artists, and this major exhibition, which opened at Tate Britain in October 2016, is an impressive retrospective of Nash’s career, taking us through his different artistic phases, exploring his inspiration drawn from landscape and his connections with modern art and surrealism. Whilst Nash is known primarily as a war artist, there are in fact only 15 paintings from those periods on display here; this is not billed as an exhibition solely concerning his war art; many of his most famous war paintings are here, but visitors may feel short-changed from the £15 entrance fee if they have come only to view his iconic images from the two major world conflicts of the 20th century, writes Sarah Warren-MacMillan. (See also our regular feature on war artists this month on pages 108 – 110)

This retrospective is thoughtfully curated, and visitors would be missing a trick if they made a direct beeline for his war art alone as progression through the nine rooms show how Nash adopted elements of almost every artistic movement, and how his wartime experiences influenced much of his later work. Biographical details about Nash are sparse throughout, and no mention is made of his younger brother, John - also an official war artist - who often worked alongside him in the studio. Nevertheless, there are frequent extracts from Nash’s letters and writings, which give us a greater insight into his thoughts and inspirations.

The first room of the exhibition concentrates on his early works, largely drawings and watercolours of landscapes. Visitors, however, might pause to study the very first exhibit, The Combat (1910), clearly influenced by William Blake, which Nash later identified as the beginning of a preoccupation with ‘aerial creatures’ that endured throughout his career, and became so evident during the Second World War.

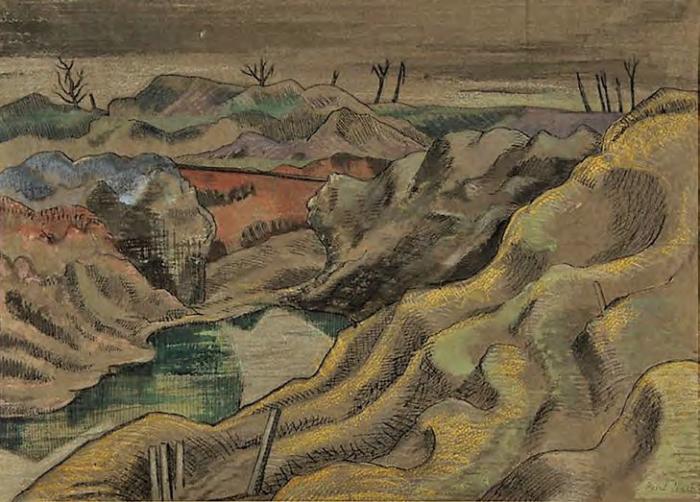

It is in Room Two, ‘We are Making a New World’, where we are shaken out of the idyllic, dreamlike world characteristic of Nash’s initial work, and are faced with seven of his most powerful pieces from the First World War which prove that - even in the midst of battle - Nash’s feel for the rhythms of landscape were ever-present and when Nash arrived at the Ypres Salient in March 1917 as an officer in the Hampshire Regiment, it was during a relatively quiet period with minimal shelling. He was initially struck by the ability of nature to regenerate the battlefield, as depicted in Spring in the Trenches, Ridge Wood (1917), exhibited here. After breaking a rib falling into a trench, Nash was sent back to England in May 1917; only a week later, his division was all but annihilated in an assault on Hill 60. On display is his homage to his comrades in arms, The Landscape - Hill 60 (1918), a scarred landscape of earth and water ravaged by shell-fire, with dogfighting aeroplanes and explosions in the sky.

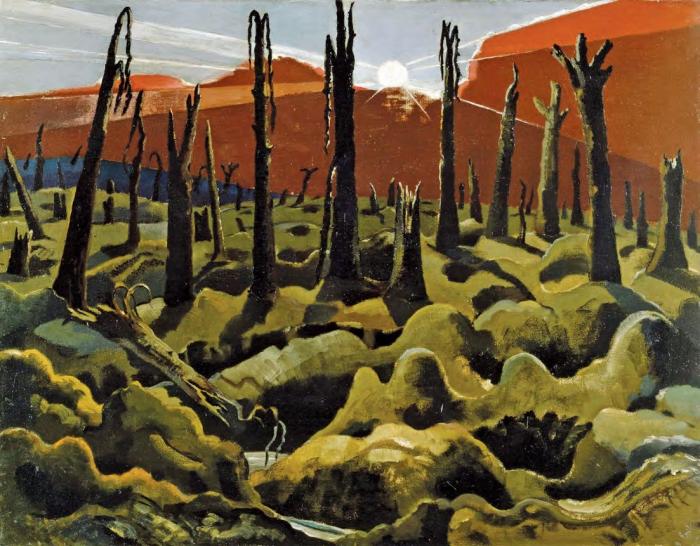

Nash returned to Belgium as an official war artist at the end of October 1917, complete with batman and chauffeur, but faced an alien environment of craters, shattered trees, and mud in the aftermath of the Battle of Passchendaele - a direct contrast to the one he had left the previous spring. Nash was outraged at this desecration of nature, producing a frenzy of ’50 drawings of muddy places’, as he called them, which he later used as the basis for a series of paintings commissioned by the Ministry of Information and the Canadian War Records Office. On his return to England in December of the same year, he also began to work with a new medium, oils.

Of those paintings on display here, the most immediately powerful, and familiar, is the bitter and ironically titled We are Making a New World (1918), with its sun rising through a red mist onto a landscape of shell-holes and blackened tree stumps. Also exhibited is Wounded Passchendaele (1918), unusual in Nash’s work, as it depicts soldiers at close hand in a gangrenous landscape.

However, the room is dominated by a huge canvas, The Menin Road (1918-19), some five and a half square metres in size, again with broken trees and heavy shafts of sunlight, zigzagging trenches, and soldiers dwarfed by the scene of destruction surrounding them.

A display cabinet containing letters to his wife from the front gives a deep insight into his mental state: ‘No pen or drawing can convey this country…sunset and sunrise are blasphemous mockeries to man.’ (13 November 1917), and a wonderful edition of Richard Aldington’s poetry Images of War (1919), with illustrations by Nash.

Nash’s art provided a new and startling vision of war. Very few of his war paintings depict dead soldiers or bodies; his outrage at the waste of life was expressed more through a portrayal of the violation of nature, and of the landscape being an innocent victim of the conflict.

Paul Nash at Tate Britain runs until 5 March 2017. (Our thanks to Tate Britain for the use of images used in this news feature)

In the aftermath of war, Nash was diagnosed as suffering from ‘emotional shock’, which is apparent in many of the paintings in Room Three from the 1920s; echoes of Flanders are evident in their landscapes, with recurring themes of ponds, resembling shell-holes, and the geometric form of seawalls at Dymchurch, redolent of zigzagging trench systems.

Throughout the 30s, Nash became a pioneer of modernism in Britain, promoting abstraction and surrealism, and founding the influential art movement Unit One with fellow war artist, Henry Moore, and others; these are covered in the intervening rooms of the exhibition, but is in Room Eight where we are shown how Nash was able to explore his dark fascination for ‘aerial creatures’. World War Two saw Nash depicting war, not from the battlefields, but through the horror of aerial warfare and the Blitz, and in 1940 he was appointed as a salaried war artist by the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC), and attached to the Royal Air Force and Air Ministry. This allowed him to further explore his captivation by flight. Nash became obsessed by ‘the rose of death’, the name the Spaniards gave to the parachute, stating that ‘When the War came, suddenly the sky was upon us all, like a huge hawk hovering, threatening. Everyone was searching the sky, waiting for some terror to fall.’ (Paul Nash, Aerial Flowers, 1945)

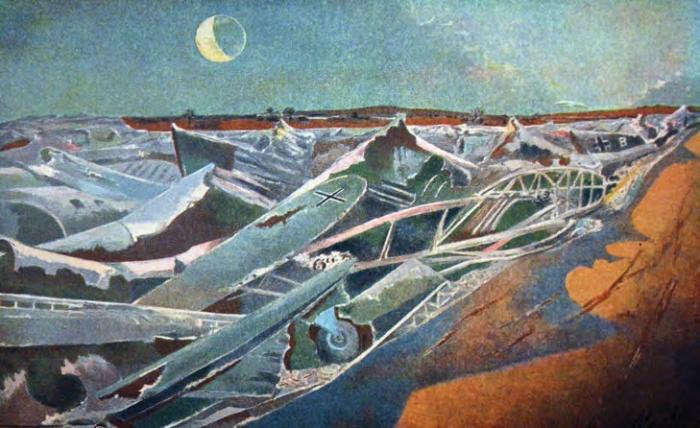

Nash was unpopular with some members of the WAAC because of the modernist nature of his work, and because the RAF wanted him to concentrate on producing portraits of aircrew and pilots. Nash went some way to appeasing them by painting a series of watercolours of crashed German aircraft, set in rural landscapes, such as The Messerschmitt in Windsor Great Park (1940) and Wrecked German Plane in Flames (Death of the Dragon) (1940), exhibited here. These crashed planes appealed to him, because they were out of their natural element, the clouds, and he described how on the ground these fallen giants took on a personified quality as monstrous creatures.

With one of Nash’s most famous paintings of the Second World War, Battle of Britain (1941) on loan elsewhere, Tate have chosen instead to display the impressive Battle of Germany (1944), a semi-abstract apocalypse interpretation of aerial bombardment and the overriding feature of this room is undoubtedly his extraordinary creation, Totes Meer (Dead Sea) (1940-1), an allegorical depiction of tangled wrecks of German aircraft, now considered one of the greatest evocations of the futility of war. The curators have cleverly juxtaposed a series of photographs taken by Nash of wrecked aeroplanes at the Cowley dump, which he used as inspiration for the painting. The dump contained many British planes, but Nash only depicted German aircraft to demonstrate the fate of ‘hundreds and hundreds of flying creatures which invaded these shores’. We are also treated to a fascinating excerpt from the Jill Craigie film, Out of Chaos (1944) which shows Nash sketching aircraft at Cowley, with a useful narrative as to how Nash’s painting was used as propaganda during the conflict.

This is a superb retrospective, which as a whole demonstrates that Nash’s war paintings were in fact part of a wider vision of portraying the landscape in new and exciting ways - and that war, along with nature, runs like a thread throughout his career