The Armstrong MT500 is losing its ‘old hack’ status and is now regarded by some as a classic; Jim Willett explains why he bought one

Over the past century, armed forces across the world have used a variety of motorcycles to perform a range of roles, both during conflict and in peace time. To a large extent, the role of the motorcycle has become less important, and only a few are left in service. Where motorcycles were a quick way to transport messages and light items by road or across country, today, bulky and sophisticated equipment takes care of the communications and requires increasingly large vehicles to transport it.

Any ex-military motorcycle can be a very practical classic to own; relatively cheap to buy, run and insure, simple to maintain and takes up little space.

Military motorcycles are not drastically different from their civilian counterparts. Matt green paint, extra bracketry for luggage and minor modifications to the electrical system are the only common details which stand out when a military specification machine is compared to a civilian trail bike. This makes them every bit as practical as the civilian machine, with the added interest of military history. In addition, the British Army envisaged the Armstrong as a general purpose motorcycle; therefore it had to be at home on long roads and tracks as well as capable when crossing rough terrain.

This has resulted in the MT500 being more comfortable over long distances than civilian trail bikes, set up predominantly for off-roading and shorter commutes.

Prior to starting production of the MT500 in 1984, Armstrong-CCM Motorcycles had taken on the licence to build the MT500’s predecessor, the Can-Am Bombardier, for military customers. Armstrong-CCM could trace their heritage back to building modified BSAs for off-road competition in the 1970s and they continue today as CCM Motorcycles, still working with both civilian and military customers.

Originally built in Canada, the Can-Am Bombardier was lightweight and agile, but its Austrian-built 250cc two-stroke Rotax engine was not ideal for military service. Like the Bombardier, the MT500 used a Rotax engine, but this time a more suitable 481.3cc four-stroke version. Despite being assembled in Lancashire, the Armstrong was quite a multi- national beast. The design seems to have been based on that of an XN Tornado from the recently defunct, Italian manufacturer SWM. Some parts were also Italian, as well as British, German and the Austrian Rotax engine.

The Rotax engine is both one of the MT500’s assets and the source of its major flaw. As with most air-cooled four-stroke singles of the era, the 481.3cc unit is reliable and has a sufficient spread of torque to chug along just off tick-over, or to blast up to, and comfortably maintain, the national speed limit.

In the 1980s, the Rotax was by no means outmoded, with features such as a balancer shaft, magnesium casings, four overhead valves and a belt-driven camshaft. Despite this specification, maintenance and repairs remain simple, most fasteners are off-the-shelf metric items and the engine is ‘safe’ in the event of timing belt failure (the valves will not contact the piston).

The Achilles heel of the MT500 however, is poor starting: with no electric start, the left hand kick is renowned for needing more than a few prods to coax the engine into life. Aside from being mounted on the left, the starting lever is easily swung, even without use of the de-compressor; just as well, as plenty of kicks can be required to get the engine running.

Many owners have developed techniques to get their bike to start in a couple of kicks if well set-up. It is conventional wisdom that starting is improved when the factory Amal carburettor is upgraded to a Dellorto or Mikuni item. My current MT500 is fitted with the Dellorto carb and the previous one had a Mikuni, but both could still be obstinate starters.

Being ex-military, fuel systems have often suffered due to ingress of sand and dirt off-road, poor fuel and the effects of being left unused for long periods, either during, or after service. A thorough strip and clean of the entire fuel system considerably improved starting on my current Armstrong. Its predecessor however, could be so stubborn, that its starting procedure became quite an attraction at rallies; much kicking, spark plug changing and pushing would cause enormous hilarity among onlookers. A sense of humour and a large left leg are essentials for prolonged Armstrong ownership.

The standard five-gear ratios are quite close; first is low enough for gentle green lanes, and most A-road hills can be negotiated in fifth, although when riding at 60-70mph, the engine sounds quite busy. A sprocket change to raise or lower gearing for commuting or serious off-roading, respectively, would be beneficial, but the factory set-up is definitely best if the bike is to be used as an all-rounder.

The front and rear drum brakes are, at best, adequate. While reliable, many owners choose to upgrade to disc brakes to improve stopping distance.

Wheels, suspension and other components are all of a decent specification and stand up well to on or off-road use all year round. Offroad knocks are soaked up well and relatively light weight and low seat height ensure that the bike remains sure-footed across rough terrain.

The last batch of Armstrong MT500s was delivered to the British Army in 1987 before production rights were sold to Harley-Davidson. When Harley-Davidson’s MT350 entered service alongside the remaining MT500s in 1993, it had received some small but significant upgrades. Although the smaller capacity engine offered marginally less performance, this was more than offset by the welcome addition of an electric starter. The MT350’s front and rear disc brakes were also a very worthwhile improvement and fitting an MT350 front end has long been a popular modification for 500s. In fact, walking around a recent MT Riders Club event, all machines present had been fitted with electric starters and front disc brakes.

My MT500 was released from the MoD in 1997, so would have served alongside MT350s for its last four years. The British Army continued to buy MT350s until 2000, with numbers in service gradually diminishing from then on. The supply of both Armstrong and Harley-Davidson versions direct from the MoD has now dried up, so bikes will have to be obtained from civilian sources. You may still come across a machine which has not been registered for road use since its release, but most will now have civilian registration numbers and have been used by one or more civilian owners.

SPECIFICATIONS

Make Armstrong

Model MT500

Nationality British

Year 1987

Production Run 1984-1987

Engine Rotax

Type Four-stroke single cylinder, single overhead camshaft

Fuel Petrol

Displacement 481.3cc

Power 32bhp@6200 R.P.M.

Torque 38Nm@5500 R.P.M.

Transmission Manual

Type Constant Mesh

Gears Five

Transfer Box N/A

Suspension Aluminium tele-hydraulic front and twinshock swinging-arm rear

Brakes Drums

Wheels Alloy hub and rim with steel spokes. Security bolts prevent tyre turning on rim

Tyres Enduro 90/90 R21 front and Enduro 4.00R18 rear Crew/seats Rider only

Dimensions (overall)

Length 2140mm

Width 835mm

Wheelbase 1445mm

Weight 161kg/354lbs (Dry unladen)

Modifications:Dellorto carburettor

Additional Notes:Bought as a project in 2016 having been stood for several years. First registered in 1997. MoD history unknown.

Owners Club:MT Riders Club: www.mtridersclub.co.uk

This has resulted in bikes on offer having varying degrees of modification and conditions being anything from concourse restorations to basket-case projects. This is reflected by a wide range of asking prices, all of which have risen sharply over the past five years: Today, it will take some searching to find even a project bike for under £1,000, yet in 2012 I got less than this for a running MT500 with six months MOT.

Despite the increased prices, MT500s remain one of the cheapest big trail bikes on the market and many have led hard lives as off-roaders or winter commuters.

Most parts are readily available from specialist suppliers, but can be expensive to buy, whether new or secondhand.

Even the latest MT500s are now 30 years old, so they have every chance of being worn out or of having been heavily repaired, so check carefully the quality of any work completed previously. Rising prices over the past few years mean that genuine, complete, really cheap MTs seldom become available. However, this does not stop them representing good value for money as they are still at the top end of the ‘old bike’ price range and are only just beginning the transition to being priced as a classic. Furthermore, a 1980s classic is a far more usable proposition than slower and more outdated bikes from earlier decades. For this reason, prices can only continue to rise and now is as good a time as any to get an Armstrong yourself.

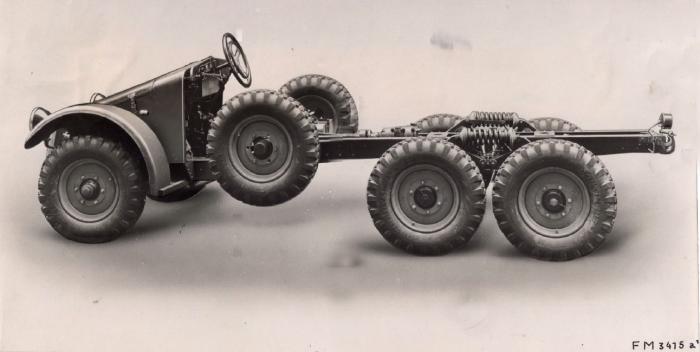

The 6x4 Krupp-Geländewagen L2H43 (Kraftfahrzeug 69) in rolling chassis form. It was designed by Friedrich Krupp AG in 1933 with an innovative coil-sprung independent rear suspension system. Power came from an air-cooled, M304 four-cylinder ‘boxer’ 60bhp petrol engine of 3308cc displacement that made it capable of up to 70kph. The side-mounted spare wheels would rotate freely to assist with off-road use. The sloping bonnet earned the truck, which was supplied with a variety of bodies especially those for artillery and signals roles, the nickname of Krupp-Schnauzer - ‘Krupp Snout’ - from German soldiers. It was also referred to as the Krupp-Protze - Kruppe Limber. Production ran from 1934 until 1936 when the improved L2H143 was introduced and production continued until 1942.