This fully kitted out SAS-style Land Rover 110 pays tribute to the First Gulf War

Few vehicles speak more of the valour and fortitude of the Special Air Service (SAS) in battle than the ‘Pinkie’. This 1989 110 Land Rover Hi-Cap pick-up, complete with the sort of equipment the SAS would have taken behind enemy lines in Iraq in 1991, is a clever replica of those which saw active service during that conflict.

Stripped down and fitted with a Rover 3,528cc V8 engine for extra power and speed in tight spots, the Land Rover 110 converted by Glover Webb of Hamble and adopted by the SAS Mobility Troop from 1985 as their Desert Patrol Vehicle, got its name after the original ‘Pink Panther’ Series IIA 109in Land Rover. Of course the SAS Land Rovers seeing active service in the Gulf in 1991 weren’t pink and were painted in desert camouflage of sand and a dark blue. They were however, central to the operation which Peter Ratcliffe describes in Eye of the storm (Michael O’Mara Books 2000) as: “The biggest gathering of SAS personnel in a battle zone anywhere in the world since the end of the Second World War.”

The SAS would, as Peter ‘Yorky’ Crossland relates in Victor Two (Bloomsbury 1996): “Be fighting behind the lines just like the original World War II SAS back in David Stirling’s time. The main difference was the firepower we carried - enough to take on and destroy just about anything we could find. Hopefully, whatever mayhem we caused would force the Iraqis to deploy large forces in order to locate us, just as Stirling had achieved with the Germans in North Africa.”

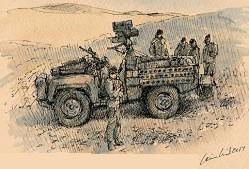

The 110s were at the heart of the mission, built to a tougher specification than civilian 110 Hi-Caps. They carried two spare wheels, had roof, doors and windscreen removed and a sturdy roll bar fitted behind the two front seats. All the lights were painted out to ensure the patrol could not be seen at night.

The 110s carried sand channels, lashed to the sides and some vehicles were fitted with powered winches. Stowed inside and outside were Jerrycans of petrol and water, rations, ammunition and other essential equipment. According to Crossland, the amount of personal equipment a real SAS operation carries is “vast” and they were supported by a Unimog, stripped out to carry the bulk of the ammunition, stores and vehicle spares.

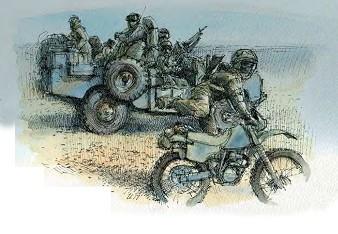

Motorcycles were vital for recces and passing messages along the column, radio silence as important as those painted-out lights to conceal an SAS presence behind enemy lines.

The substantial armoury varied from one Land Rover to the next. Mounted on the bonnet of Ratcliffe’s vehicle, was a 7.62mm GPMG and on a mounting behind him, facing rearwards, was a World War Two 0.5in Browning M2 heavy machine gun. They also carried an 8mm mortar, a grenade launcher, their personal weapons (M16s) and a Milan anti-tank missile launcher

LAND ROVERS AND THE SAS

Formed in 1941, Lieutenant David Stirling’s L Detachment Special Air Service (SAS) Brigade was the first really effective special forces unit in the British Army, transported by the Long Range Desert Group, they destroyed 60 aircraft on three airfields in Libya. Further North African successes followed and in Italy, supporting the Allied Landings. By D Day in 1944, they used their own armed Jeeps and along with the French SAS caused mayhem behind the enemy lines. Disbanded briefly after World War Two, by 1956 the new 21 SAS Regiment numbered five squadrons with the Malayan Scouts renamed 22 SAS Regiment in 1952.

Post- war, Land Rovers became the natural choice for vehicle deployment and for short range operations in Oman, 88in wheelbase Series One Land Rovers were stripped down and fitted with twin Vickers machine guns on a raised commander’s seat.

A.30 calibre machine gun faced rearwards and was manned by the vehicle’s radio operator.

From 1967 the SAS progressed to the Series IIA 109in Land Rover which could carry more and support longer range operations than the Series One.

Painted a dusky pink which was a very effective desert camouflage, these ‘ Pink Panthers’ or ‘Pinkies’ remained in service for nearly 20 years, equipped first with the Vickers and. 30 cal machine guns, which were phased out in favour of general purpose machine guns and Browning. 50 calibre heavy machine guns. The latter carried these forward as part of the armoury for the coil sprung, V8 110 HCPU (High- Capacity Pick- Up) which replaced the Pinkie in 1985 to become the SAS Desert Patrol Vehicle until the end of Land Rover’s 110 production in 2016.

Designed for ease of access to weaponry, the Land Rover’s one disadvantage in sub-zero conditions was that it offered no shelter against the wind and sleet. Initially, thanks to inadequate forward intelligence, troops froze while wearing the desert tunics and shemaghs they were issued with but later, supplies of local goatskin coats were sourced and these doubtless saved lives.

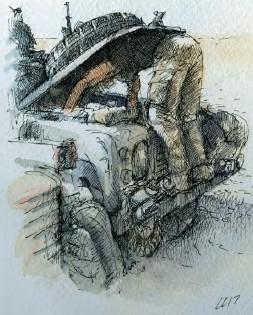

Mechanical problems were mercifully few as Mike Curtis describes in Close Quarter Battle (Transworld Publishers 1998): “The track rod ends are stuffed. They’re getting bent by the rocks. It’s a miracle we didn’t break one.”

Mobility Troop had an ingenious solution to straightening them. They took them off, wrapped plastic explosive around the track rods and lit them to create some heat. Then they bent them back into shape.

Minimising any losses of the heavily-armed Land Rovers was uppermost. Accidents however did happen especially when the troops were sleep-deprived, as Crossland relates: “We had been driving for two hours when… the sound of metal hitting metal rang out; the rear vehicle had run into the back of a Unimog…the collision had wrecked the radiator on the Land Rover and shunted the dashboard over on to the passenger side, where the officer in charge was sitting.”

Luckily, serious injury was avoided but the driver had fallen asleep at the wheel and on inspection the Land Rover was beyond repair and had to be abandoned. But not before they’d taken two wheels off for spares, de-rigging it completely before concealing it with rocks, dirt and a spare camouflage net.

Driving errors could have cost lives and Ratcliffe recalled a getaway across a steep bank: “We charged towards the berm and raced up the side. Then, just as we reached the top, Mugger let the revs drop and we stalled right on the crest, rocking slightly back and forwards.”

Winching the vehicle back down cost valuable seconds and, with the enemy only 600m away, “with the revs rising to a howl we surged forwards…at the top, the 110 leapt the crest, flipped nose down and we were suddenly rushing and sliding down the far side and onto the road.”

Later, leaving after a successful operation where tow chains had been used to silently extract fibre-optic cable from beneath a manhole cover, Crossland, concentrating on rocky terrain co-drove off a ridge into a ravine. He managed to jump clear as the vehicle bounced and leapt into space and watched horrified as the Land Rover rolled completely over.

Fortunately Pat, the driver, was protected by the roll bar and the high-mounted Browning machine gun saved the two men in the rear from injury any more serious than broken ribs. With all the Jerrycans, ammunition and stores safely back in the righted Land Rover, the 110 carried on its way.

Writing about the same incident, Ratcliffe commented later: “They were amazing vehicles, those Land Rovers. We refuelled Pat’s battered 110 once it had been checked over and it started first time. We didn’t experience a problem with any of them.”

Operating with the Land Rovers under camouflage netting could be cramped, especially when there was enemy engagement but they were essential to success, as Cameron Spence observes: “Four bodies battling to get organised in a camouflaged tent, ninetenths of which was filled with fighting vehicle. I hunkered down behind the front of our vehicle, elbows propped on the bonnet, my 16 trained on the advancing column of dust.”

Later, the camo nets would stay wrapped around the roll bar. Friendly fire having wreaked havoc elsewhere, they could not take the risk of being hit by the coalition fighter jets and instead spread large Union Jacks on the ground at Lying-Up Points.

The 110s’ speed, manoeuvrability and resilience, together with their formidable firepower saved skins when the patrols were compromised while successfully destroying Scud communications installation Victor Two in early February 1991.

It was usual to do daily checks of tyre pressures, oil and water levels and clean as much sand as possible from the weapons. Mobility Troop was charged with the repair and servicing of the Land Rovers and very few were lost by the time Saddam had backed down sufficiently for orders to be given for the SAS to withdraw.

THE SAS IN THE GULF WAR 1991

The UN set a deadline for Saddam to withdraw from Kuwait by January 15, 1991 or face military action. Talks in Geneva had broken down by January 9 and on January 15, the US made the first statement launching Operation Desert Storm with the first air strikes taking place on January 17. Commander in Chief of the Allied Forces in the Gulf, General Norman Schwarzkopf was sceptical of any role Special Forces might play, remembering his poor experience of them in the Vietnam War.

The SAS were ready at Victor, their forward operating base in Saudi and Sir Peter de la Billiere, once an SAS director of operations and now commander of the British Forces in the Gulf would ensure a role for the regiment. Hunting the Scud missile launchers that had already started bombing Israel was a huge responsibility for the SAS. Peter Ratcliffe put it succinctly: “Singlehandedly, 22 SAS had been tasked with saving the coalition, which would undoubtedly fragment if Israel struck at Iraq.” They crossed over the border into Iraq’s western desert unnoticed in late January 1991.

Squadrons A and D were split into half squadron units of about 30 men, each allocated eight Land Rover 110s, a Mercedes Unimog and as many motorcycles as they needed. B Squadron was similarly split with one half remaining at Victor to tackle any anti-British terrorist activity and the other sub-divided into eight-man patrols, two setting out on foot. One of these was given the call sign Bravo Two Zero and much has been documented about this patrol’s fate.

A key target, again the subject of written accounts from members of Alpha One Zero patrol was Victor Two, a Scud communications installation which turned out to be much more heavily defended than intelligence had suggested and for the SAS it was a classic operation, planting explosives and making a fighting withdrawal under cover of fire from the Land Rovers. Following the success of Victor Two over February 7-8,1991, and coinciding with a resupply convoy between February11-17, Peter Ratcliffe as RSM called an extraordinary sergeants’ mess meeting at Wadi Tubal on February 15, partly as sergeants from all squadrons would be there and importantly, to reinforce discipline and emphasise to all that the SAS did not falter under fire.

Audacious and extraordinary it may seem to onlookers, for the regiment it was business as usual and General Schwarzkopf’s signature is on the minutes. He was impressed. The letter of commendation from General Schwarzkopf concludes that the exemplary performance of the SAS was: “In keeping with the proud history and tradition that has been established by that regiment.”

CORNWALL MVT’S SAS V8 110 HI-CAP

Although this 1989 110 Hi-Cap pick-up is an expertly built replica, there are a number of genuine parts including the Milan missile launcher and the MIRA thermal imager, along with inert ammunition. The other weaponry is also genuine including the general purpose machine gun which, like everything else, is of course deactivated. In addition to the equipment which came with the Land Rover, the current owner has sourced a Browning. 50 calibre heavy machine gun and a pintle mount for the rear which he understands was used on a Sherman tank in the film Fury.

The offside wing sports a beautifully painted cartoon depicting the Pink Panther as a crusading knight, wielding a bent lance and atop a sorry nag, an exasperated, sweating Inspector Clouseau depicted as Saddam Hussein.

For more information on the Military Vehicle Trust go to www.mvt.org.uk and for Cornwall area activities see www.cornwallmvt.co.uk

After a gruelling operation in which the SAS regiment lost a total of four men, withdrawal from Iraq at the end of February 1991 was poignant as well as momentous. Ratcliffe describes the occasion: “As we were about to pull out for the border, I took my crew’s Union Jack which had been spread out as usual on the ground near my wagon and tied it to the aerial behind the driver. The crews of the other vehicles followed suit, and as we neared the border we must have appeared like some ancient band of crusaders emerging from the desert with colours flying.”

Daring and brave as they were, without the Land Rover 110 Hi-Cap 22 SAS Regiment may well have struggled.

Further Reading

Storm Command

General Sir Peter de la Billiere (Harper Collins 1992)

Bravo Two Zero

Andy McNab ( Bantam Press 1993)

The One That Got Away

Chris Ryan (Century 1995)

Victor Two

Peter (Yorky) Crossland (Bloomsbury Publishing PLC 1996)

Sabre Squadron

Cameron Spence (Michael Joseph Ltd 1997)

Close Quarter Battle

Mike Curtis (Transworld Publishers Ltd 1998)

The Eye of the Storm

Peter Ratcliffe DCM (Michael O Mara Books Ltd 2000)

The Real Bravo Two Zero

Michael Asher (Cassell and Co 2002)

Soldier Five

Mike Coburn (Bullet Publishing and Media 2004)